What is compound interest?

Benjamin Franklin said “Money makes money. And the money that money makes, makes money.” Outside of the egregious use of the words ‘makes’ and ‘money’ – this is the primary concept of compound interest. The concept can be deceptively easy to understand, deceptive in its true power which is not as intuitively grasped. Easily put – money (or principal) + consistency + interest + time = significant profit. This is not the true formula (which is Compound Interest=Principal×(1+Annual Interest Rate)^NumberOfYearsApplied−Principal – note the exponent which is where the compounding occurs), but I hope it simply explains in an easy to understand way what it takes to create a winning compound interest moment.

What is the difference between (simple) interest and compound interest?

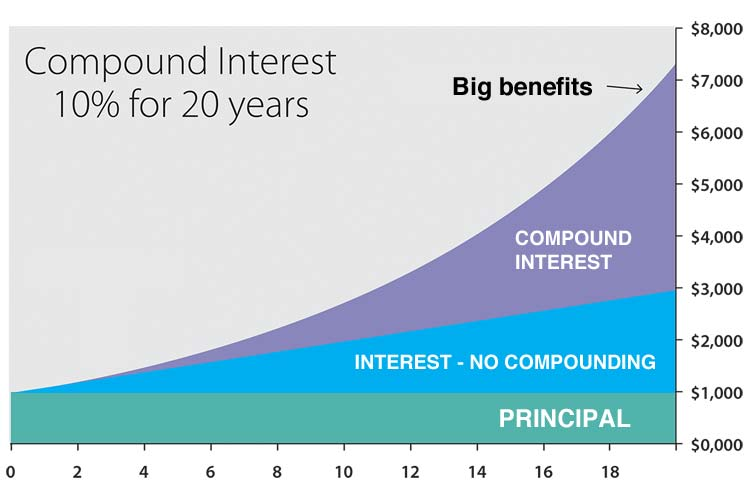

Simple interest, or generally said ‘interest’ is defined as the cost of tying up money. Looking at it from a lender perspective, the lender charges an interest rate (either fixed meaning unchanging or variable meaning changing based on pre-defined criteria over time) which will profit the lender for tying up or making their money inaccessible to them for a period of time. The borrower agrees to pay that interest because the borrower needs the money and they accept the costs of doing so – as set by the lender. Generally speaking, simple interest takes only the original amount (or principal) to calculate the interest-related funds over time. Taking the image above as an example, if I were to borrow $1,000 at a 10% interest rate over 20 years – I will have ultimately paid $3,000 to the lender over the 20 years, $2,000 of interest (i.e. the charge the borrower has for the opportunity of borrowing the money) and $1,000 of the original principal (i.e. the original amount borrowed). Not a bad deal for the lender, but 20 years is a long time to keep your money tied up!

Compound interest is tied to an annual interest rate (or annually compounding interest rate / APR / Annual Percentage Rate) which rewards the lender or investor of the money for keeping it tied up over time. The simplest way I like to think about this is tied to savings accounts. Let’s take the picture above as another example for compound interest. So let’s say you start a savings of a savings account with $1,000 placed in it year 1 and you choose to completely leave it alone over a 20 year period. Let’s also say that you find a savings account with a 10% annual interest rate (if you ever find that, please do let me know!). The key is the annually compounding interest rate. By the end of the 20 year period, your initial $1,000 will have grown to around $7,000. There are great calculators online (example) that showcase the power of compound interest with numbers you can plug in and play with.

I’m trying to keep this simple, but I want to touch on taxes and inflation. Each item could have its own long-form discussion but if you want to have a solid sense of the money you’d be walking away from over time you need to consider taxes and inflation. Inflation is a rate over time that influences the buying power of (for me) the US dollar $. A simple example is that a 10% inflation rate if I invest $100 for 1 year, at the end of that year my initial buying power of $100 will really buy the equivalent of $90 at the end of the investment. Not so good, right? So you need to make sure that the inflation percentage is lower than the interest rate if you are lending money. Taxes are another facet to consider. The US government wants a piece of any profitable income I have (based on whatever tax bracket I happen to be in) which influences the overall profit I will walk away with. There’s a ton that can be said and a lot of complexity here, but high level these items should be considered so you know what you’re walking away with at the end of the day.

Sidebar – Mortgages and Amortization Schedules

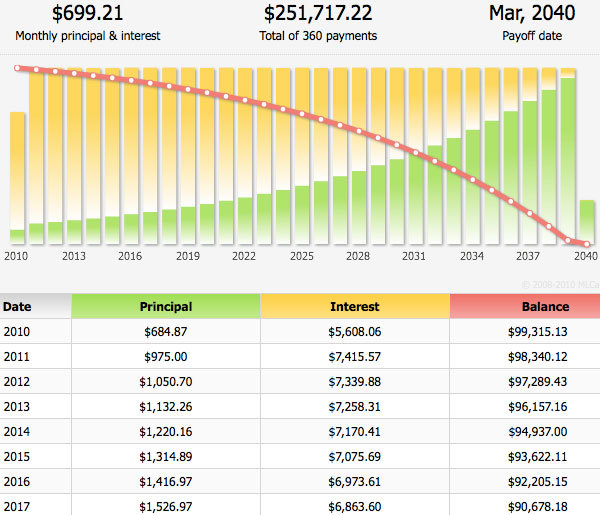

Considering compound interest, another interesting financial area where a lot of money is made is home mortgages. I remember when I was very young one of the first things I remember learning from my father was something called an amortization schedule. My father was horrified, insulted, and generally upset by how much money he was losing over time based on his mortgage and payoff schedule. He has a saying of ‘if it’s mine, I want it and if it’s yours I want you to have it.’ This is something that’s stuck with me and honestly, I agree with this perspective. Why? Take a look at the above image. The principal is the same as what we were talking about before, in this context it’s paying down the total amount you borrowed. Interest is solely the cost of the privilege to borrow the money. Out of the initial 2010 payments of $6,292.93 (Principal $684.87 + Interest $5,608.06), only 10% of the over $6,000 go toward paying down the debt! As can be seen above, it’s a sliding scale so by the end of the loan (this is a 30-year mortgage example) the situation reverses and nearly all of the payment goes toward principal – though have you heard commercials pushing the benefits of refinancing your home mortgage? 90% interest for the first year with 10% going toward principal? That guarantees a nice income and longstanding customer with minimal effort on your end as a business, sounds ideal looking at it from a lender perspective. As a borrower, it feels incredibly predatory and not great.

Now, this is a very simplistic view. This quick paragraph doesn’t take into account taxes and insurance (which your mortgage payments will for your home purchase) nor does it look at the differences between variable vs fixed interest rates. To be fair, there are some very valid reasons to refinance your home (in my opinion mostly surrounding changing life circumstances to enable a lower monthly payment) – though make no mistake that to do this you’re going to absolutely pay for the privilege of doing so in ‘closing fees’ and a significant amount of interest in the first few years. Considering the average US homeowner stays in their home 13 years (reference) – roughly 10 years where I live – an average US citizen pays a tremendous amount of interest throughout their life and assuming the average person doesn’t pay off their loan early, never sees the final days of paying mostly the principal vs interest to truly own their own home.

Today’s practical relevance

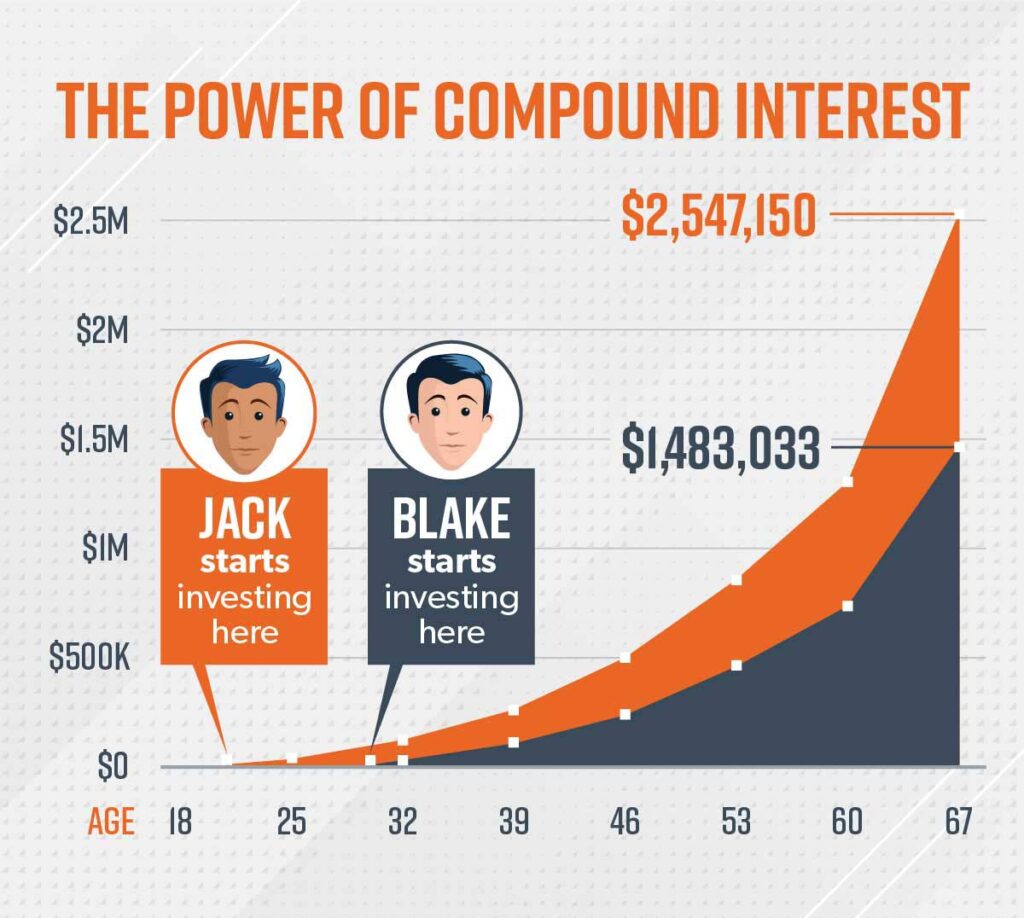

Whether you’re talking about saving or investing, the earlier you can start and the more consistent you can be the better off you’ll be long-term. The above image is the best representation that I can find. Looking at Jack who started investing at about 20 vs Blake who started investing around 30 has an over $1M dollar difference but the time they hit retirement age. Why? Compounding interest assuming all other things are equal. There’s a significant amount of power behind compound interest and I hope this brief high-level look helps inform why!